-

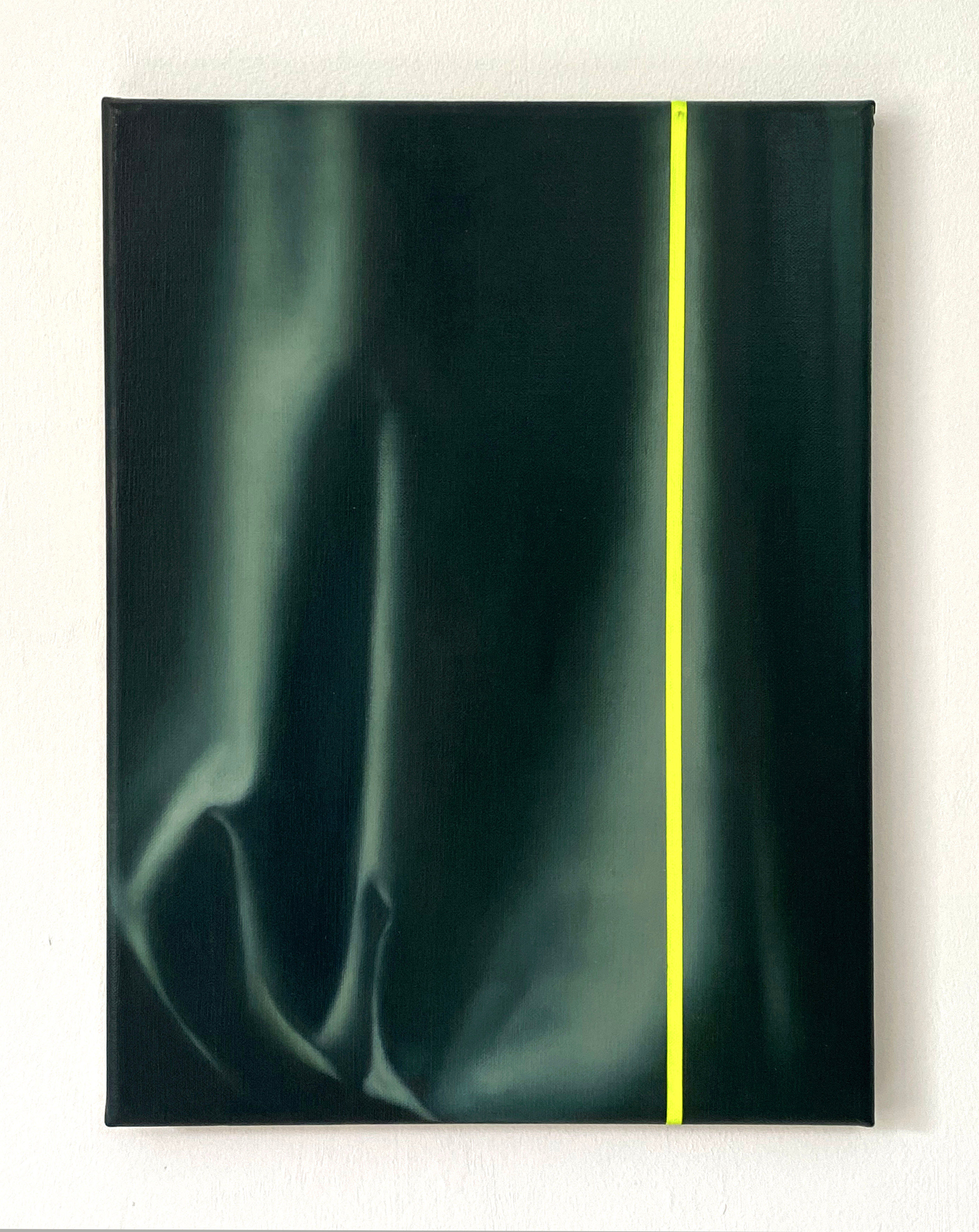

Stage II - Shortlisted for the John Moores Painting Prize 2023 and exhibited at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool

Stage II - Shortlisted for the John Moores Painting Prize 2023 and exhibited at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool -

CF: How did this series start and how did it evolve from previous work?

HK: This series began during lockdown when we were largely confined to the domestic space. As time slowed my focus shifted to the oversized set of faded grey velvet curtains hung in my bedroom. Curtains seemed to hold particular resonance during lockdown, a symbol of a closeted, detached, psychological space, a protective but inhibiting demarcation of the boundary between us and the something, or maybe nothing, that lay beyond view. Drawn curtains, theatrical or domestic, automatically invite speculation as to what is behind, what might be revealed. This ongoing body of work sprung from the 100s of photographs I took of these curtains, and has now widened to include further domestic ‘coverings’ in the form of upholstery and wallpaper.I’ve always been interested in fragmentation, the gaps, what cannot be seen, and the dislocated nature of recollection, a fragile anchorage, the close proximity between being something and then nothing. This current body of work evolved from a previous series using the photograph as a starting point. Asteroids & Figurines were paintings based on the blurry, sometimes barely readable online images of domestic ceramic figurines and asteroids, all abandoned forlorn objects, cast adrift on eBay and in space, their purpose outlived, on the edge of disappearance.

-

CF: You talk about your fascination with our relationship to the photographic image, how did this materialise and how do you incorporate this into your work?

HK: My use of the photographic image began at art college in the 1980s where I made Super 8 films of heavy drawn theatre curtains, and creating huge photographic prints from single Super 8 frames from the film, blown up to the point where the image began to break up, becoming abstracted resembling brush marks in a painting, like a detail of drapery in an old master. Since then the film still and photograph have been the starting point for all my work. (This also attests to the cyclical nature of ideas in that curtains have re emerged in my work nearly 30 years on.) I became more interested in the idea of holding a moment in time, or rather how the camera held it, then reproduced it, which touches on our wider relationship with the photograph and how it brings the past into the present. Photography is quick, painting is slow. I like the idea that the act of painting could stretch and expand that moment in time.My fascination with our relationship to the photographic image materialised in a body of work titled Delayed Rays of a Star 2018, 30 paintings and a film made from a single photograph of my mother that I had found after her death. An unremarkable photo, it nonetheless struck me with the German-Jewish critic and philosopher, Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) described as “the posthumous shock”, an extraordinary affirmation of her presence. This project became a forensic excavation of a photograph involving sifting, scanning, scrutinizing, dissecting, magnifying, repeating and reproducing to uncover what was beyond reach, questioning how little of the image needs to be apparent to derive meaning. This has become the process by which I use the photographic image in my work but now working from often multiple images and fragments which are assembled, reassembled and collaged together to find new connections, looking for something that suggests transformation.

-

CF: It could be argued that photography is defined not by what it gives us but what we give to it, it is a starting point for our own perceptions. What kind of emotional response do you hope people have when viewing your paintings?

HK: "Leaving space in the work, a way in for the viewer’s imagination, is important for me, not to be too prescriptive, both in terms of what I am conveying or inducing a specific response. Even if a project stems from a deeply personal photograph as in the Delayed Rays of a Star, as I mentioned earlier, I want to be able to take the disparate elements excavated from that photograph or photographs somewhere else, to reassemble them, shifting perspective and scale, to detach from the specifics of the original image and give them another life. So while a sense of unease, melancholy, or fragility might pervade the work, it's detached from intense emotions, so it opens up to interpretation. I don’t need the viewer to know where what they see has come from, it's enough for me to know.

That said, I do hope that all the fragments of folded fabric, curtains, pitted velvet upholstery and faded wallpaper that I bring together in the current paintings somehow suggest new connections, and meanings, a sense of unease perhaps, a tenuous anchorage, a potential unravelling - the familiar on the verge of becoming something else, what French writer, philosopher and literary theorist Maurice Blanchot described as “unrevealed yet manifest”. -

CF: What is it about the soft furnishings and wallpaper referenced in this work that holds such resonance with you?

HK: It's not that I’m particularly drawn to soft furnishings per se but one form seems to have followed another in terms of what has captured my attention – a set of curtains, and a patch of faded wallpaper in my bedroom, some old dusty deep buttoned banquettes and a black plastic sheet in the bar of an old working mens club where I had my studio for a few months. I now found myself in this strange micro realm of soft furnishings!

Curtains, wallpaper, and upholstery are all soft or softening forms of boundary within our interior spaces. I’m interested in how these mute coverings, whether thinly papered or densely layered and padded act as a screen or veil, a protective, opaque but tenuous barrier to what cannot be seen, beyond, beneath or behind. I’m drawn to the idea of papering over the cracks, a holding on and blocking out, layers to be unravelled, there is an unsettling melancholy to what are for me immersive micro landscapes within the details of these surfaces that connect to the underlying and ongoing theme of fragmentation in my work.

. -

CF: We love the contrast between the soft, velvety curtains you paint in this series and the harsh single fluorescent line in each of these paintings. Can you tell us about those? Do you see yourself as a figurative painter or abstract or do you straddle both?

HK: I don’t really think about being either a figurative or abstract painter, probably because the often binary distinction between them isn’t all that instructive, so the short answer would be I straddle both. The artist, Amy Sillman says there's no such thing as representation, that everything in a painting, scale, space etc is some form of synthetic construction, of abstraction. The starting point for my work is the isolated detail from single or multiple photographs, and once detached from a wider reference. It's not always clear what they are or were part of beyond the shapes and colours – I do like the idea of the every day being unfamiliar, things being on the edge of recognition or becoming something else.

The fluorescent strip is an attempt to introduce a jolt, a harsh blankness that might indicate a void, in direct contrast to the more sensual recesses and folds of the curtains in the rest of the painting, a way of reinforcing my interest in the proximity of something and nothing, memory, presence and absence, the real and imagined, the notion that by drawing back the screen or peeling away those protective layers our fragile anchorage might give way. -

CF: How does your painting technique relate to the ideas you explore in your work?

HK: Much of the exploration and development of ideas for a painting are undertaken before I begin to paint. It can be a lengthy painstaking process of scrutinising multiple images, isolating details, printing out, ripping up, reassembling, digitally manipulating rephotographing collaged fragments, until I feel I have something close to what I want to convey.

The paintings themselves are rendered with as little paint and as few brush marks as possible through the application of multiple layers of very thin oil glazes, thinking of it, as I paint, as a fragile layer of pigment over a blank surface, echoing the construction of a photograph. This can translate physically during the painting process, as I sometimes find myself holding my breath when applying the paint to the canvas, in case breathing might create a mark too heavy handed, too material. This experience highlights for me an interesting contrast in scale between a physical thing and an idea - a literal and symbolic proximity of something and nothing. I have this quote from the artist Robert Morris which I love on my studio wall , “Over and over again the mark gathers itself as a kind of membrane over absence”.